I found the section in Beginning Theory about Vladimir Propp's philosophy particularly interesting, because it reminded me of a British Literature class I took two semesters ago here at TCU.

In that class, we learned about the various stages of the hero narrative. At the time, I thought it was fascinating that so many stories could fit into the same structure. Now, I find myself looking at the whole of literature through the lens of literary theory. True, Propp's categorization refers specifically to fairy/folk tales, but I'm sure similar lists of elements/events could be made for just about every literary genre.

So, then, we return to the tenet which says that all forms of art are interrelated. No new literature is completely new, but is rather a reworking of that which has already been done. It is the same story over and over again, only with slightly different characters which may, at first glance, appear original, but really just fit into a pre-established mold which we have come to expect.

Reflections

on literary theory

Monday, November 22, 2010

Monday, November 15, 2010

Postmodernism in a nutshell

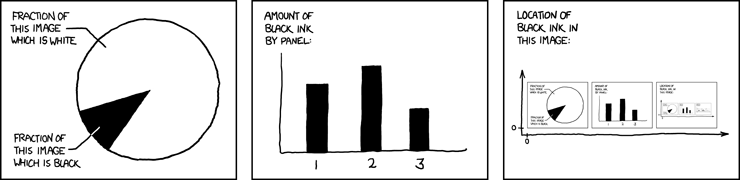

I stumbled across this webcomic the other night, and could not help but make the connection to the readings from this week, particularly the chapter in Theory Toolbox about "Posts." This is a perfect example of postmodernism: graphs which are about nothing other than themselves.

At first, I have to admit that I was downright alarmed to be thinking about literary theory outside of class, but I then realized that this is the whole point of learning about it: to be able to apply theoretical lenses in everyday life.

I will never be able to view ironic Internet graphics the same way again. Who knew that Internet geeks were really modern-day literary theorists in disguise?

Monday, November 8, 2010

The Construction of Time

Time.

Such a small word.

Such a big impact on our lives.

The "Space/Time" chapter in The Theory Toolbox raises some interesting questions about our concept of time.

The authors of the book allege that time is merely a social construct designed to keep the proletariat under control.

I disagree.

Sure, the historical reasoning presented in the chapter may have laid the foundation for the eight-hour workday we are familiar with today, but I'm sure many of you would agree that there are other, more immediately practical reasons for the nine-to-five grind.

For example, this eight-hour schedule has the populace working during the daylight hours, when less artificial lighting is used, thus saving electricity.

Secondly, our workday takes place during the daylight hours because our bodies are designed to respond to darkness with lethargy, and to bright light with awareness. Therefore, we work during the hours in which we are most alert and able to carry out our jobs best.

The other reason why time is not a social concept is because it is based on nature. Some of the ways we visualize time, such as the three-hundred-sixty-degree clock face, are merely representations, not absolute truths.

However, the base concept of measuring time, the Earth's location in relation to the Sun, is a natural absolute: the Sun appears to rise, and the Sun appears to set. It takes three hundred sixty-five of these sunrises and sunsets before we experience the exact same hours of sunlight and darkness.

Therefore, the Sun is our natural measurement. The rest is just a series of happy patterns discovered by some mathematicians with way too much time on their hands.

Such a small word.

Such a big impact on our lives.

The "Space/Time" chapter in The Theory Toolbox raises some interesting questions about our concept of time.

The authors of the book allege that time is merely a social construct designed to keep the proletariat under control.

I disagree.

Sure, the historical reasoning presented in the chapter may have laid the foundation for the eight-hour workday we are familiar with today, but I'm sure many of you would agree that there are other, more immediately practical reasons for the nine-to-five grind.

For example, this eight-hour schedule has the populace working during the daylight hours, when less artificial lighting is used, thus saving electricity.

Secondly, our workday takes place during the daylight hours because our bodies are designed to respond to darkness with lethargy, and to bright light with awareness. Therefore, we work during the hours in which we are most alert and able to carry out our jobs best.

The other reason why time is not a social concept is because it is based on nature. Some of the ways we visualize time, such as the three-hundred-sixty-degree clock face, are merely representations, not absolute truths.

However, the base concept of measuring time, the Earth's location in relation to the Sun, is a natural absolute: the Sun appears to rise, and the Sun appears to set. It takes three hundred sixty-five of these sunrises and sunsets before we experience the exact same hours of sunlight and darkness.

Therefore, the Sun is our natural measurement. The rest is just a series of happy patterns discovered by some mathematicians with way too much time on their hands.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)